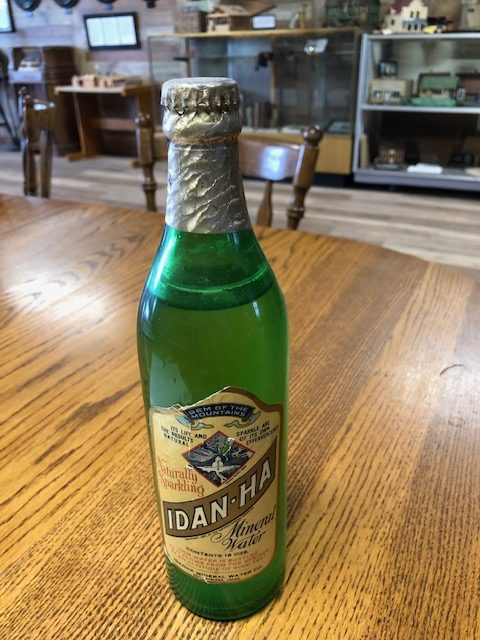

Courtesy US FWS, John & Karen Hollingsworth, Photographers

The Brigham City grackles had long, V-shaped tails. Dick explained that three grackle species are native in the US. Florida’s boat-tailed grackles are found along the east and gulf coasts and common grackles are found mostly east of the Rockies. Mexican or great-tailed grackles have become the most common in developed areas of the West; although, according to eBird and UtahBirds.org, both common and great-tailed varieties frequent Utah.

Grackle species are also distinguished by their size and color: between a robin and a crow in size, they are about the same length as American crows, but not as heavy. Common grackles have more varied colors and long tails. Boat-tailed grackles have dark eyes; whereas great-tailed males are iridescent black with piercing yellow eyes. Female great-tails are dark brown above and paler below, with a buff-colored throat and a stripe above the eye. Juveniles have coloring similar to females with a dark eye.

Omnivorous, grackles forage in fields, feedlots, golf courses, cemeteries, parks, neighborhoods, and parking lots. Trees and reeds near water provide roosting and breeding sites where larger males claim their flock’s territory with song.

Great-tails have an unusually large repertoire of vocalizations that are used year-round. Flamboyant males perform a wider variety, while females engage mostly in chattering sounds. “Chut” from females and “Clack” from males warn of humans or other predators. Even though most female calls are low-key, there are reports of females singing their own territorial song.

Because they are loud, and large numbers of birds can leave great deposits of droppings, grackles are often considered pests. This designation is especially true in Texas and other southern states where flocks of 100,000 or more roam parking lots.

And they are smart! Icterids, the New World blackbirds, including bobolinks, meadowlarks, ravens, crows, and grackles are set apart from many birds by their intelligence. Grackles adapt their behavior with experience and habitat. The Audubon website notes: “They are clever foragers: Great-tailed Grackles can solve Aesop’s Fable tests, dropping stones into a container of water in order to sufficiently raise the level to pluck out a prize ….”

Sometimes I enjoy stepping back and observing parking lot ecology. I look for grackles. Then I marvel at how our world would look and smell without birds to clean up after us. Above all, I enjoy hearing male and female great-tailed grackles singing in the trees or watching them forage between cars. Take five and give it a try!

I’m Lyle Bingham and I’m Wild About Utah

Credits:

Photos: Courtesy US FWS, John & Karen Hollingsworth, Photographers

Featured Audio: Courtesy & Copyright © Friend Weller, Utah Public Radio upr.org

Text: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading: Lyle Bingham, https://bridgerlandaudubon.org/

Additional Reading

Lyle Bingham’s Wild About Utah Postings

Great Tailed Grackle, AllAboutBirds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great-tailed_Grackle

Great-tailed Grackle – Quiscalus mexicanus, Utah Birds, Utah County Birders, http://www.utahbirds.org/birdsofutah/ProfilesD-K/GreatTailedGrackle.htm

Other Photos: http://www.utahbirds.org/birdsofutah/BirdsD-K/GreatTailGrackle.htm

Great-tailed Grackle, Field Guide, National Audubon, https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/great-tailed-grackle

Everything is bigger in Texas: Grackle Flock at a Grocery Store in Houston-Courtesy YouTube and KHOU Houston Channel 11